A ‘lost decade’: 1990s

The early 1990s saw a growing critique by irrigation engineers of under performance of irrigation engineering design specifically in sub-Saharan Africa. This led to major efforts to re-think how engineers should work with small-scale farmers using more ‘participatory’ methods. Lucas Horst at Wageningen University in the Netherlands led an exemplary initiative on this.

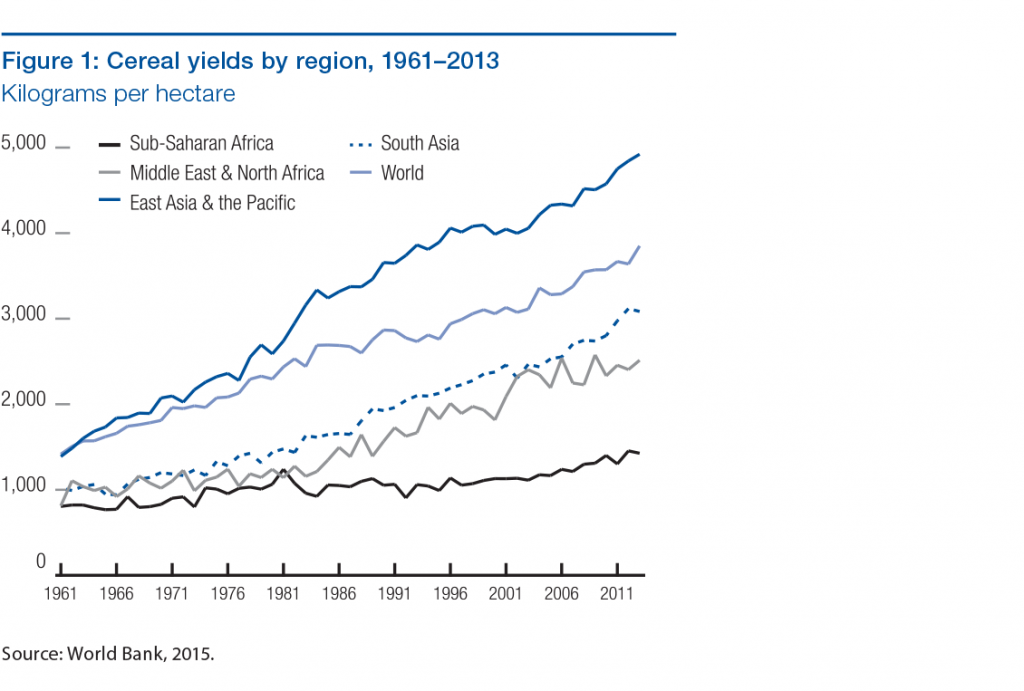

There was widespread concern that African agriculture was stagnating and falling behind Latin America and parts of Asia. However, as international food commodity prices were falling and it was still relatively cheap to import food to the large coastal cities of Africa, agriculture did not get the investment it needed.

As a result, there was a hiatus in irrigation and agriculture investment by both national governments and international donors in the 1990s. Instead, policy focused on institutional and regulatory reform in order to achieve ‘integrated water resource management’ (IWRM) to mediate competing demands for water at the scale of major river basins, with a strong emphasis on water conservation.

Early 2000s

At the turn of the century, new continent-wide initiatives promoted the need for improved agricultural water management.

For instance, the African Union’s development program, the New Partnership for Africa’s Development’s (NEPAD’s) Comprehensive Africa Agriculture Development Programme (CAADP) identified irrigation development as one of the focus areas for pursuing increased and sustainable productivity in agriculture. The UK government’s Commission for Africa in 2005 also advocated massive investment in irrigation development.

The CAADP promoted the revision of national irrigation policies and an increase in national agricultural budgets.

Thanks to this continent-wide approach, investment in irrigation rapidly increased despite the problems of the previous decade.

In 2006, a rising oil price and a boom of biofuel production (supplied by cereal and oilseed crops) created a rapid rise in food prices. This exposed weaknesses in the functioning of international food markets to increase trade in times of scarcity. There was a sudden interest in food production and investors became interested in what was seen as profitable, irrigable, land.

Foreign governments and commercial investors attempted to acquire large tracts of land in areas where land was cheap, often in Sub Saharan Africa. This was widely criticised as threatening to displace existing communities – a process known as ‘land grabbing’. The availability of water for irrigation was a critical factor for investors.

Higher agricultural prices (and hence increased costs of food imports) also re-energised pan-African efforts to improve agricultural productivity. International bodies and African governments dismissed concerns about ‘land grabs’ with promises of new technology, increased training and job opportunities. They sought rapid agricultural expansion through foreign investment in large-scale farming. Governments made ambitious plans for irrigation to increase agricultural productivity on a large scale by creating special planning powers in development areas and ‘growth corridors’ such as the Beira corridor in Mozambique and the Southern Agricultural Growth Corridor in Tanzania –SAGCOT.

However, also in this period, growing evidence emerged of dynamic, private irrigation, on a small scale (between 0.5 and 5 hectares), where individual farmers used pumps to irrigate commercial crops. 65,000 pumps were imported into Ghana alone between 2003-2010.

Much of this small-scale irrigation is unofficial and not recorded in official statistics. However, improvements in remote-sensing satellite technology have enabled analysis of images that have greater resolution – improving from 10km in 2006 to 10m in 2016. Thanks to the emergence of satellite data and improved resolution, studies by IWMI showed that irrigated area in sub-Saharan Africa is actually two or three times greater than previously thought.

Growing recognition of the importance of irrigation initiatives by small-scale farmers in transforming agricultural livelihoods in sub-Saharan Africa has prompted international support for ‘farmer-led irrigation development’, exemplified by the World Bank:

Finally, it was realised that the problem of irrigation design was rooted in practitioners’ approaches to understanding farmers.

A growing number of irrigation engineers recognise the importance of involving farmers in the process of irrigation design. They have begun trialling participatory design and farmer management, and exploring more bottom-up, grassroots approaches that recognise farmers’ own technical knowledge.