A farmer-led irrigation development approach allows for users and engineers to co-design and create sustainable irrigation solutions that can be achieved by farmers themselves. This approach uses two circular learning processes that form the basis for the (farmer-led) ‘Participatory Irrigated Agricultural Development’ (PIAD) approach developed by Wouter Beekman and Gert Jan Veldwisch.

An iterative learning process

For participatory irrigation planning with farmers, it is critical that the impetus for the project must come from farmers themselves.

Central to farmer-led irrigation development “must be their own rationality, their own ‘wheel’, in combination with critical, consensus-based self-analysis by the users, amidst both diverging and shared interests” (Boelens and Dávila 1998, p. 427).

Designing an irrigation development should be an iterative process of information exchange, discussion, negotiation and collective decision-making about the future use and related technical features of an irrigation system between the farmer and the actors engaging with that farmer. This ensures that social elements are taken into consideration.

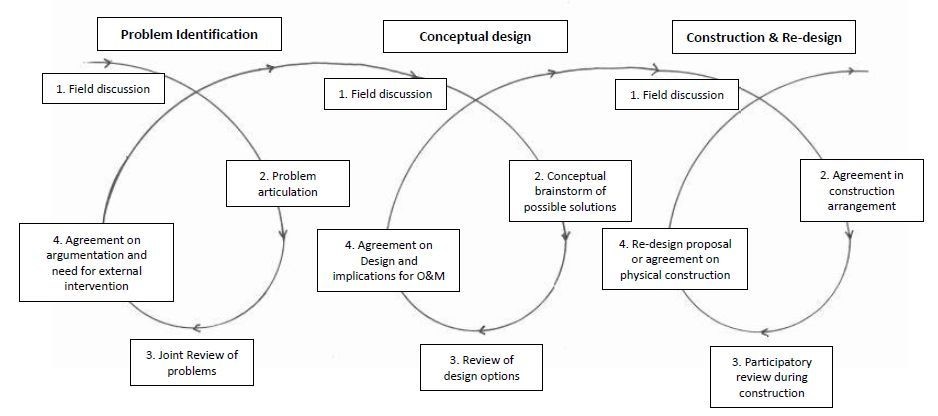

A suggested approach is that the communication between engineers and farmers can be formalised in learning cycles with planned engagements between the groups around decision points (Scheer, 1996).

Learning cycles will differ between the engineers and farmers. They may revolve around the same topic and formalised communication is necessary to foster mutual understanding.

A learning cycle is an iterative process that advances in spirals while a constant renegotiation, redefinition of the problem and redesign takes place until the intervention is finished, and often even beyond.

The irrigation design process consists of three phases:

- Problem identification.

- Conceptual design.

- Construction and re-design.

Problem identification phase

The activities in this phase aim to reach a shared analysis of current irrigation practices, potential improvements and solutions.

Irrigation practices are seen as combinations of infrastructure, management processes and institutional arrangements around water management, but also include agricultural production processes and market relations.

It is important to repeatedly question why users perceive a proposed intervention to be necessary, because it helps clarify their analysis of the problem. This results in a process of pushing back and forth between the farmers, trying to externalise their management problems through infrastructural interventions by the project, and the engineer internalising issues as essentially rooted in the management or regulatory domains, until a consensus is reached of what can only be solved technically and what can be solved organisationally. The aim of this process is to formulate the design criteria.

Conceptual design phase

This phase is a continuation of the discussions undertaken in the problem identification phase, in which initial ideas for possible solutions have been raised. However, it is also a distinct phase, as the focus changes from analysing existing problems, to thinking about solutions. It involves comparing and analysing different solutions with varying combinations of institutional and physical change.

An important discussion during this phase concerns the roles and responsibilities during construction and use of the systems by different actors. This discussion clarifies what types of structures are to be constructed, what materials are needed and who does what during the construction.

This feeds into discussions on how the project’s operation and maintenance (O&M) is to be organised after construction, and to what extent it requires a change (or re-design) of organisational structures to facilitate it.

This discussion is critical because many rules and regulations in a farmer-led irrigation system are determined by the initial investors or owners, and additional investments by projects are liable to cause organisational change through shifts in “ownership”.

The result of this phase is an agreement on what to construct, who takes particular actions and who contributes in the construction phase.

Construction and re-design phase

The start of this phase is marked by the signing of a three-party contract between the engineer/project, the constructor and the farmers. While actual construction activities start soon after the signing, the design activities continue.

The construction phase is an integral part of the iterative process of designing, where new insights acquired during construction lead to further re-design. Even after extensive discussions and visualisation, designs remain very abstract and difficult to understand for many farmers. This can be particularly acute if the proposed solution is one that users are not familiar with. For example, explaining hydraulic principles is difficult to convey without a constructed example.

The process of re-designing during construction is an important element in the appropriation by the farmers of the improvements. It allows for learning cycles through practice and the close interaction with the contractor and engineer, deliberately attempting to put farmers in the driver’s seat.

Conclusion

The learning cycles inherent in this iterative approach not only function as a form of project management, but are also supportive of efforts to strengthen local conflict management techniques as translated into operations and maintenance regulations.

These processes are relatively time-consuming (and expensive) when implemented at a small scale, but have good prospects for scaling-up when actively building on the learning processes.

This is backed up by research showing that large-scale projects focusing on small-scale interventions might lead to better results, allowing for active involvement of the farmers in all the design and construction phases. This approach allows for active investments by the users, both in design and in project costs and labour, which subsequently results in the maintenance and replication of the improvements.

Key messages:

|

Suggested further reading:

- Costs and Performance of Irrigation Projects: A Comparison of sub-Saharan Africa and Other Development Regions.

- Mozambique – Sustainable Irrigation Development Project (PROIRRI): environmental and social management framework.

- Supporting Farmer-Led Irrigation in Mozambique: Reflections on Field-Testing a New Design Approach.

- Full Reference List

Acknowledgements

- Wouter Beekman, Resiliência Moçambique